Japanese Anarchist Federation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The was an

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

organisation that existed in Japan from 1946 to 1968.

Formed in May 1946, shortly following the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the JAF was plagued by disputes between anarcho-communists

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains res ...

and anarcho-syndicalists

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in ...

. These divisions culminated in its dissolution in October 1950. By 1956, anarcho-syndicalists reconstituted the Anarchist Federation, while anarcho-communists formed their own Japan Anarchist Club.

The JAF was involved in direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

in numerous forms, including anti-war agitation against the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

and Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, and protests

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of coopera ...

against the 1960 Japan-US Security Treaty and the 1965 Japan-South Korea Treaty.

While anarchism gained support within the Zengakuren

Zengakuren is a league of university student associations founded in 1948 in Japan. The word is an abridgement of which literally means "All-Japan Federation of Student Self-Government Associations." Notable for organizing protests and marches, ...

and Zenkyoto student groups during the 1960s, the Japanese Anarchist Federation remained a small organisation with little direct influence, and resolved to dissolve itself in 1968.

Another group calling itself the Anarchist Federation formed in October 1988.

Context

Anarchism in Japan

Anarchism in Japan began to emerge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as Western anarchist literature began to be translated into Japanese. It existed throughout the 20th century in various forms, despite repression by the state that becam ...

has a long history, arguably having roots in the egalitarian structure of some communal villages during the Tokugawa era

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characteri ...

. Its modern form, however, originated in the political activities of Kōtoku Shūsui

, better known by the pen name , was a Japanese socialist and anarchist who played a leading role in introducing anarchism to Japan in the early 20th century. Historian John Crump described him as "the most famous socialist in Japan".

He wa ...

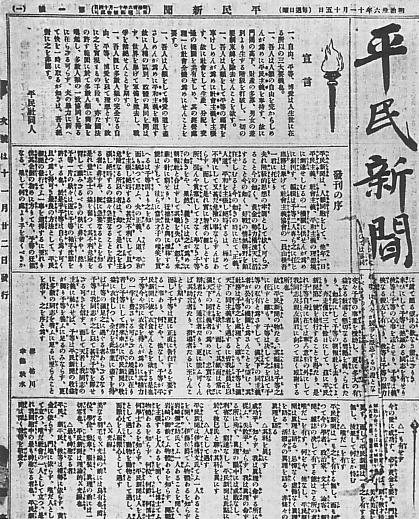

, an anarchist who edited the libertarian-socialist newspaper ''Heimin Shinbun

(also spelled ''Heimin Shimbun'') was a socialist and anti-war daily newspaper established in Japan in November 1903, as the newspaper of the Heimin-sha group. It was founded by Kōtoku Shūsui and Sakai Toshihiko, as a pacifist response to th ...

'' in the early 20th century. He gained the permission of anarcho-communist writer Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

to translate his works into Japanese, which helped to steer the nascent anarchist movement in a communist direction.

Others in the anarchist movement gravitated towards anarcho-syndicalism. Amongst these was Sanshirō Ishikawa, who had learned syndicalist organising methods from French unions while in Europe. In contrast, advocates of anarcho-communism such as Sakutarō Iwasa

Sakutarō, Sakutaro or Sakutarou (written: or ) is a masculine Japanese given name. Notable people with the name include:

*, Japanese writer

*, Japanese anarchist

*, Japanese legal scholar

Fictional characters

*, a character in the sound novel ' ...

were strongly focused on the principles of communal solidarity and mutual aid espoused by Kropotkin. Their focus, and rejection of ideas they perceived to be antithetical to anarchism, led to anarcho-syndicalists giving their ideology the label of 'pure anarchism'. 'Pure anarchists' sharply criticised syndicalist methods and argued that - even if unions seized power, the fundamentally exploitative nature of capitalism would remain, as they argued had happened in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

.

In 1928, there was a split in the anarchist movement between these two factions, cementing their divide. As the Japanese state became more militaristic, repression of political movements such as anarchism intensified, particularly after the Manchurian Incident

The Mukden Incident, or Manchurian Incident, known in Chinese as the 9.18 Incident (九・一八), was a false flag event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

On September 18, 1931, L ...

in 1931, and organised anarchist activism essentially became impossible until the end of the Second World War in 1945.

History

Founding and split

Following the war, and the subsequent occupation of Japan by American forces, anarchists coalesced into a new Japanese Anarchist Federation in May 1946. Both anarcho-communists and anarcho-syndicalists joined, conscious of trying to mend their pre-war division. Many of the leading figures were the same as before the war, with both Sanshirō Ishikawa and Sakutarō Iwasa participating. Iwasa was elected chairman of the National Committee of the Federation, a chiefly organisational role. In June 1946, they began to publish a journal, named ''Heimin Shinbun'' after Kōtoku Shūsui's magazine. The organisation nonetheless failed to gain much support from the general public, due to a number of factors. Anarchists were discriminated against due to a policy of anti-communism pursued by the American-led Allied occupation force, and anarchists also faced opposition from theJapanese Communist Party

The is a left-wing to far-left political party in Japan. With approximately 270,000 members belonging to 18,000 branches, it is one of the largest non-governing communist parties in the world.

The party advocates the establishment of a democr ...

and its strong trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

presence. Land reform instituted after the war also effectively eliminated the class of tenant farmers that had formed the core base of the pre-war anarchist movement. The anarchists within the JAF were also divided over their political strategy, quarrelling amongst themselves frequently. Idealism, rather than the practical considerations of the populace, became the focus of ''Heimin Shinbun'', and this hindered their capacity to muster public support.

Tensions between the 'pure' and syndicalist anarchists resurfaced due to their lack of success. In May 1950, a splitting organisation, the 'Anarcho-Syndicalist Group' ''(Anaruko Sanjikarisuto Gurūpu)'' formed. By October 1950, the organisation had firmly split, and was dissolved. In June 1951 the anarcho-communists created a 'Japan Anarchist Club' ''(Nihon Anakisuto Kurabu)''. Significantly, Sakutarō Iwasa followed the communists in joining the Club, depriving the Federation of a central figure.

Refounding

By 1956, the Japanese Anarchist Federation had been reformed, albeit without reuniting with the communist faction. In that year, the JAF started publishing a new journal, ''Kurohata'' ('Black Flag'), which was later renamed ''Jiyu-Rengo'' ('Libertarian Federation'). Within the latter, a new anarchist theorist namedŌsawa Masamichi Ōsawa, Osawa or Oosawa (written: or lit. "big swamp") is a Japanese surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*, Japanese ice hockey player

*Eiji Osawa (born 1935), Japanese chemist

* Itsumi Osawa (born 1966), Japanese actress, writer an ...

began to rise to prominence. He advocated a more gradual revolution, focusing on the social and cultural rather than the political. His ideas were controversial, decried by some as 'revisionist', but he firmly established a more reformist strand within the anarchist movement.

Direct action

As an anarchist movement, the Federation supported direct action on multiple occasions through its lifespan. One of the most significant of these was the national opposition to the Japan-US Security Treaty in 1960. Huge demonstrations swept major cities, and theSōhyō The , often abbreviated to , was a left-leaning union confederation. Founded in 1950, it was the largest labor federation in Japan for several decades.

Origins

In the immediate aftermath of Japan's defeat in World War II, the United States-led All ...

union and others staged strikes of around 4 to 6 million workers. Nonetheless, the treaty was accepted by the government. Disillusionment with constitutional politics led the 'Mainstream' faction of the Zengakuren student movement to join with the JAF in calling for political violence as a form of protest.

A similar protest broke out in 1965 against the treaty with South Korea, with a similar result. Ōsawa commented in ''Jiyu-Rengo'' that the government's action was an 'outrage', but that this had happened repeatedly - and that each time a 'threat to parliamentary democracy' was talked about by journalists, two camps of party politicians furiously decried the other's action, but then proceeded to make a truce and ignore the problem.

Out of this disillusionment, anarchism gained ground within the protest movement, including the Zenkyoto student power movement created during anti-Vietnam War protests. The rise of protest groups encouraged the Japanese Anarchist Federation to declare 'The Opening of the Era of Direct Action' in 1968. This culminated in the occupation of Tokyo University by anarchist students for several months in 1968.

The anarchism espoused by these students was not that of the JAF, however. The 'Council of United Struggle' at the university declared that they were "aristocratic anarchists", struggling not on behalf of the worker but for themselves, attempting to deny their own aristocratic attributes by engaging in political struggle. Ōsawa, for example, approved of the use of violent tactics, but feared that it was too separated from the masses, claiming that "it would come to a new Stalinism" even if it did succeed.

Legacy

The separation of the Japanese Anarchist Federation from the contemporary political protests demonstrated the weakness of the organisation. In 1968, the organisation was finally disbanded. It resolved "creatively to dissolve" in an attempt to formulate new forms of organisation, and announced its dissolution formally in ''Jiyu-Rengo'' on the 1st January 1969. Its anarcho-communist rival, the Japan Anarchist Club, remained active until March 1980. Another group calling itself the Japanese Anarchist Federation was formed in October 1988.See also

*Anarchism in Japan

Anarchism in Japan began to emerge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as Western anarchist literature began to be translated into Japanese. It existed throughout the 20th century in various forms, despite repression by the state that becam ...

Notes

References

* * * * * {{Authority control Organizations established in 1946 Anarchist organizations in Japan Organizations disestablished in 1968 Anarchist Federations